From Lore to Foresight

Solo Exhibition at Patel Brow

May 24 –

July 5, 2025

Tkaronto/Toronto

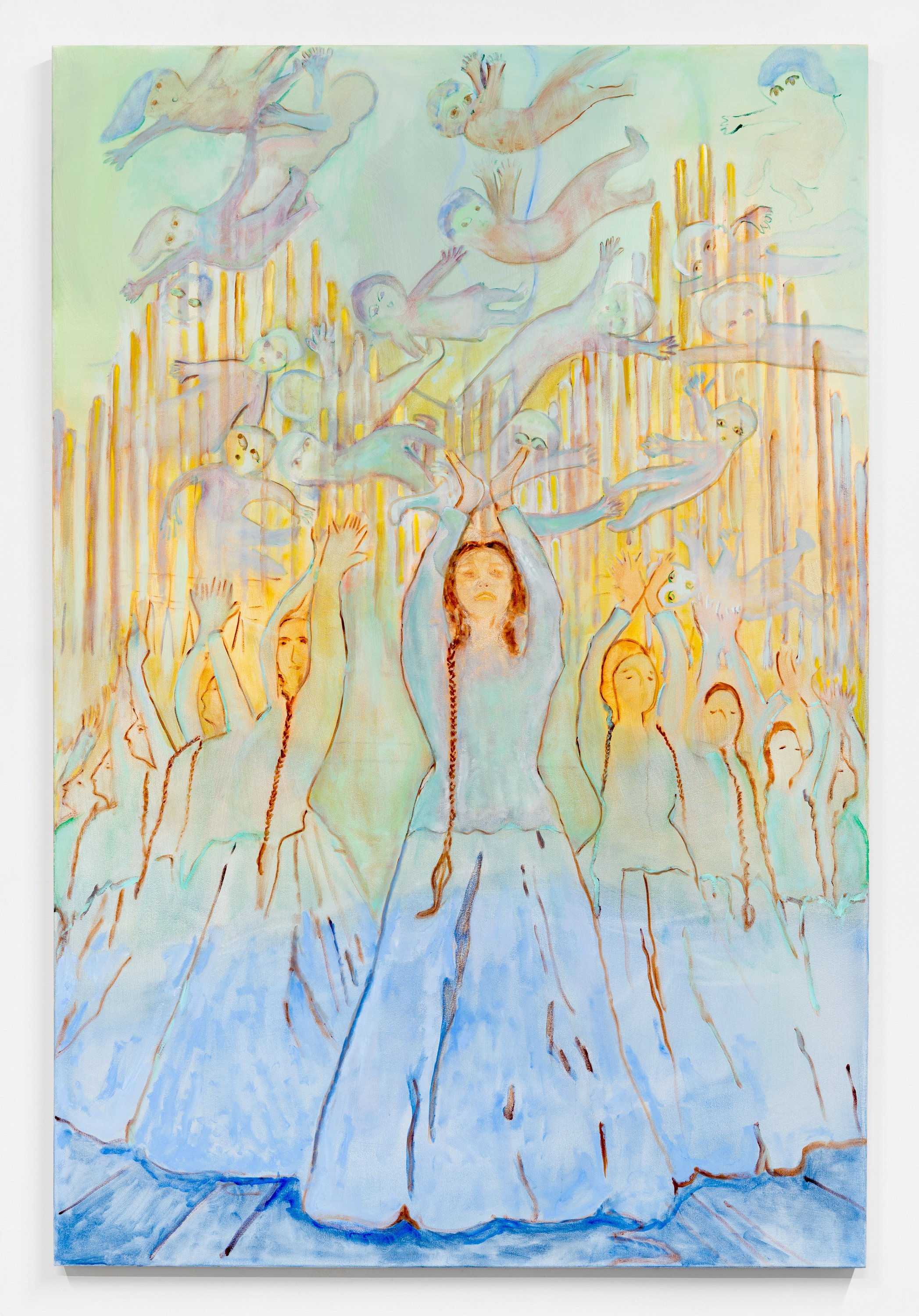

Vibrant columns and pillar-like figures swathed in robes raise their hands in supplication, offering up a sacred salute to the heavens. The silenced notes of a pipe organ ascend to the skies in the form of ghostly apparitions. Feminine figures stand in symmetrical alignment in the light, shoulder-to-shoulder with their ancestors, sentinels of the invisible but ever-present link between the worlds of the sacred and the material, the past and the present, the forgotten and the remembered. Even if history insists on their separation, these figurative bodies stand as witnesses to a different kind of narrative, and to the different possible forms of healing.

Is painting a truly solitary act? From Lore to Foresight seems to imply that even in solitude, the artist is channeling a collective heritage, especially when it is one of trauma unaddressed. For the deafening silence of unacknowledged histories and the vanished voices of the Armenian genocide are a veritable presence in every one of Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich’s works. Painting becomes a work of visual archeology, a means of preserving living memory.

The walls of her studio are covered with archival photographs, the graphic underpinning of her painterly compositions. Her process is informed by the oral histories passed down to her by her family, as well as the way trauma inhabits the body as an inheritance of generations. Her approach to the material, its superimposed layers made fragile through different treatments — faded, sandblasted, sometimes obliterated — allows for the resurfacing of distant voices and figures distorted by time.

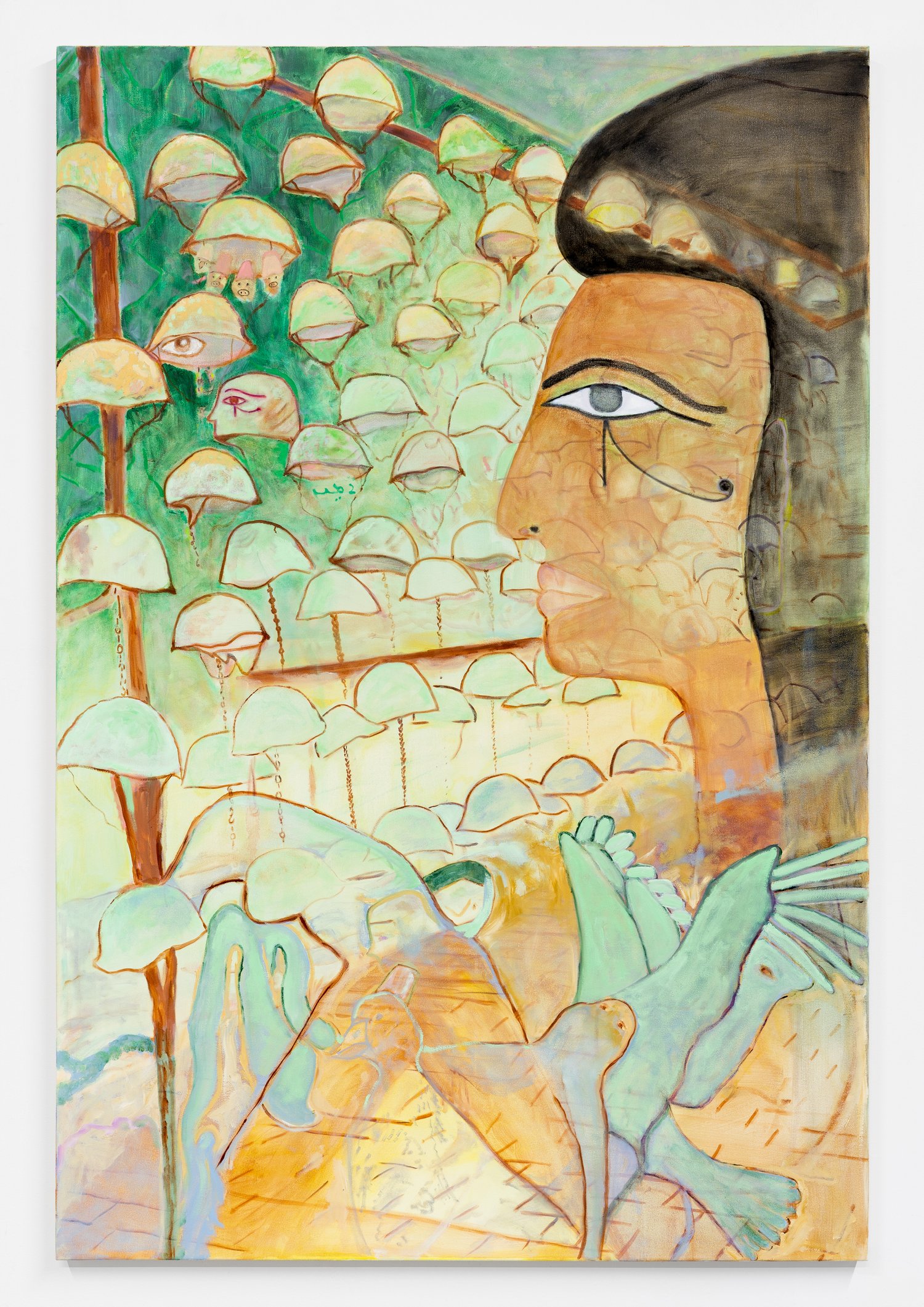

One day she came across a photo of rows of Armenian soldiers’ helmets displayed like trophies in a park in Azerbaijan and found herself transfixed. These helmets, ripped from their context, become a somber procession where each carries the weight of a life cut short. The Egyptian eye with its stylized tear (a reference to the country where the artist’s Armenian family was exiled) both witnesses and condemns — as do all the disproportional faces presiding over so many of her works. Their fixity reinforces the idea of an eternal, lucid gaze that equally surveys past and present, silently taking in all the violence that still ravages Armenia to this day.

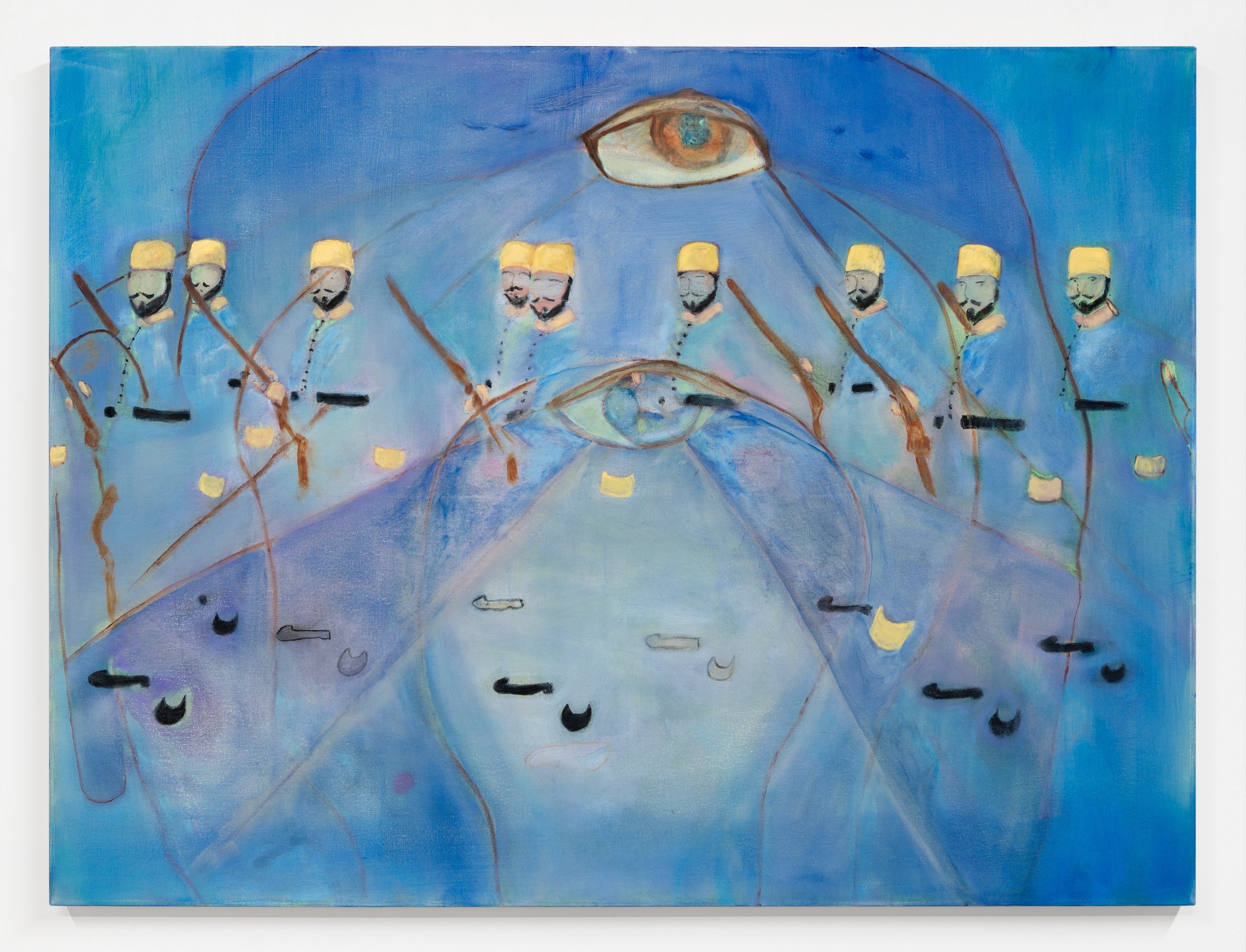

The fez, a symbol of Ottoman authority, circumscribes a group of barely sketched out female figures, while others, with their bolder lines, seem determined to resist oblivion. The piece entitled 27 echoes a memory passed down by the artist’s mother, referencing the number assigned to her grandmother at the orphanage where she ended up. It becomes a symbol of resilience, representing the only member of the family to survive the genocide.

Ahmarani Jaouich approaches charged political subjects with a destabilizing gentleness. She employs light, vibrant colors and simple forms that are deconstructed and open. Guided by her intuition, her approach is not limited to simple representation; she rather entices us to a tactile consideration of the canvas, revealing the viewer’s own vulnerability through the delicacy of her treatment.

From Lore to Foresight is an invitation to consider how that which is buried in the depths of personal and collective memory holds immense power, nurturing an inward gaze that allows us to better see what connects people to one another. Her paintings are like subterranean streams, which spring to the surface bearing that which must be seen, heard, known. They call to mind Etel Adnan’s words in her novel Night: “I measure my memory of things, but not memory itself, as the present is also overflowing.”

— Élise Lafontaine, translated by Lina Mounzer

Bloodlines

Solo Exhibition at

Arsenal New York

June 23 –

August 18, 2023

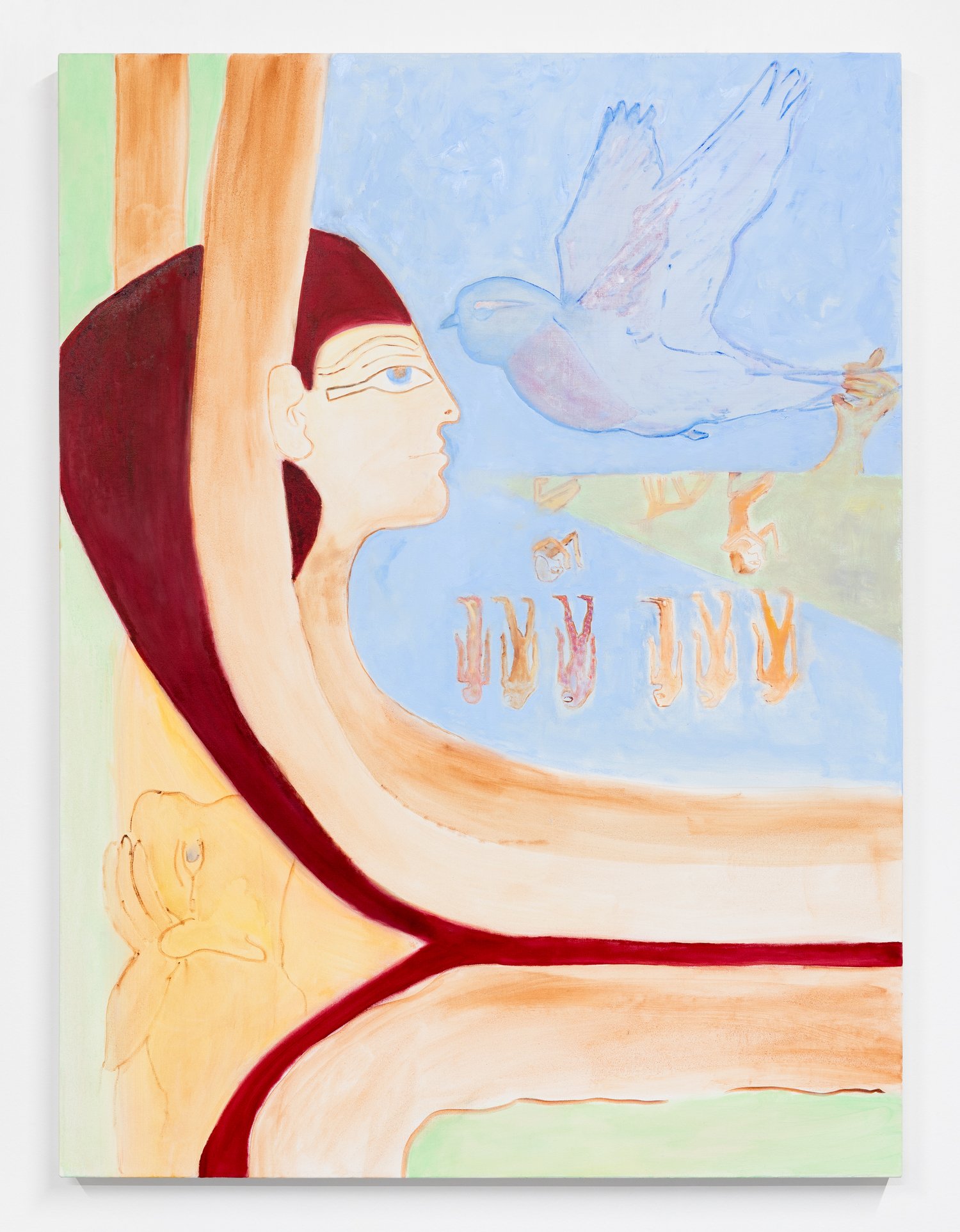

Arsenal Contemporary Art New York is pleased to present the first solo exhibition of Montreal-based artist Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich in the United States. In her work, the Canadian painter draws from her mixed heritage, being born to parents of Egyptian and Lebanese descent who are themselves children of Armenian refugees. The artist explores generational trauma, and the cultural and emotional wounds that are passed down. Working directly from her genealogy through old photographs, but also oral accounts provided by relatives, the artist explores and tries to grasp where she comes from, tracing her family’s journey through inhospitable grounds, rife with racial and ethnic discrimination. Her work is about what is left behind after exile and displacement, and what is carried through this rupture. It is about the unspoken and the unspeakable. But above all else, Ahmarani Jaouich’s work is an everlasting testament of love to her parents and her ancestors.

In her work, she traverses depths of emotion, identity and spirituality to represent feelings of longing and belonging. In this way, the exhibition opens up a space for everyone to connect with their own cultural roots, encouraging us to reflect on the ways in which our identities have been shaped by the places we call home, by the places our parents have called home.

Ahmarani Jaouich works intuitively, letting symbols and images come to her naturally during long meditation sessions to which she subscribes daily. Over the years, a glossary has emerged, symbols and figures that recur throughout her paintings. Such is the case of snakes, of fez, this traditional Turkish headcover, but also the pala bıyık, a handlebar moustache associated with the Ottomans, and many Egyptian figures. All of these function as symbolic participants in her artistic process. She threads history, memory, and emotions into alluring compositions of saccharine hues that act as channels towards her own practice of healing and remembrance. Through her expressive brushstrokes, evocative symbolism, and delicate use of color, she delivers a personal account that reverberates across generations.